When Buddhas Fall: Thoughts on Humans. Thoughts of Trees.

Living and Dying with the Methuselah Bristlecone, the General Sherman Sequoia, the Toomer's Corner Oaks, Sakura Petals, and the Tree of Ténéré.

The average lifespan of a human being on this earth is about 72 years. We outlive every other great ape—every other primate, for that matter. When it comes to life expectancy, our closest neighbors include Asian elephants, macaws, African Grey parrots, blue whales, and lobsters.

Actually, this is a pretty good neighborhood. All of the above seem like interesting creatures to hang out with (even lobsters are cool in their own way). On the other hand, many of the really long-lived animals seem batshit eccentric…the various tortoises, quahog clams, tubeworms…the Greenland sharks (that reek of urine and usually have parasitic worms coming out of their eyes)…

If I were to extend my lifespan, I would bypass the lot of them and go for the trees. Tree lifespans vary by species, but a good portion of them exist at a sweet spot of extended life—long, but not too long—allowing one to witness some serious changes in human civilizations (at this point, maybe outliving them all), yet without the worry of cooking to death when the sun goes nova, or being the last lonely being in the universe watching the brown dwarves cool.

The oldest trees are bristlecone pines. The oldest of them all, Methuselah, is nearly 5000 years old. Methuselah was born in the Bronze Age—before the first recorded writing. And it’s still with us, somewhere in Bryce Canyon National Park in California, still doing whatever nearly 5000-year-old bristlecone pines do.

Which one is Methuselah? Wouldn't you like to know. ;)*

However, neither you nor I can visit Methuselah, nor even pinpoint it with Google maps. Methuselah’s exact location, as well as the locations its elderly neighbors, is kept secret. The obvious reason is to thwart vandals, who might deface, damage, or even kill the tree.

But the danger doesn’t just come from vandals. In 1964, a doctoral student cut down a bristlecone pine named “Prometheus” to finish his research. The now-dead Prometheus was found to be even older than Methuselah.

But hey, we’re all glad that he completed his dissertation.

A little Googling reveals something interesting thing about trees: the older they get, and the more notable they become—the more likely someone will cut, topple, or otherwise kill them.

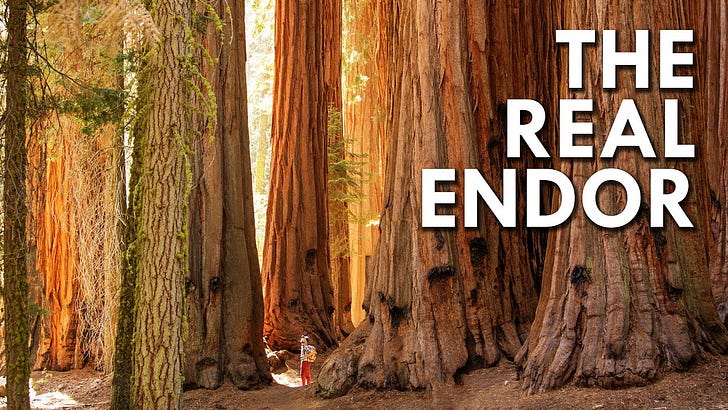

The largest of the giant sequoias can live upwards of 3000 years. The General Sherman sequoia is the largest living single-stem tree on Earth, rising nearly 300 feet above the forest floor, with a mass of about 2000 tons.

And, up to very recently, some trees were even larger than the General Sherman. Of course, these giant trees were a wet dream for loggers—and though their wood (the giant sequoias’, not the loggers') was found to be too brittle for contractors and carpenters—for a time these giant sequoias, some of the grandest and most majestic organisms on the planet, did end up providing us with a vast supply of toothpicks.

Yes, toothpicks.

Sometimes you just wonder—was anyone thinking?

The Tree of Ténéré was an acacia. It was neither the oldest, nor tallest tree. Next to the General Sherman, it would have been downright puny. But it was not next to the General Sherman. Nor was it next to any other tree…for nearly a hundred miles in all directions.

Located in northeast Niger, in the middle of the Sahara Desert, the Tree of Ténéré was the most isolated tree on earth.

The sole survivor of a more temperate age, the Tree of Ténéré had been revered as a signpost, a lighthouse in the desert, even a miracle, for at least three centuries. Its roots reached more than 100 feet beneath the surface. Even European explorers wrote of it with wonder, and noted it on their maps.

Until 1973, when it was knocked over by a truck.

The only tree in over 27,000 square miles, and it was hit by a truck.

It is said that the driver was drunk.

This monument stands in the place of the original Tree of Ténéré (pictured above).**

Trees far closer to home have met similar, head-scratching fates. In Auburn, Alabama, there is an intersection called Toomer’s Corner. There, two oak trees grew. The Toomer’s Corner oak trees had been there for 85 years, and the Auburn University community would celebrate football victories by "rolling" them with toilet paper.

This was celebratory, and in no way harmed the trees. What did harm them, however, was a fan of the rival University of Alabama. In 2010, this fan used a powerful herbicide to kill the Toomer’s Corner oak trees.

When asked why he killed the trees, his response was, “I wanted Auburn people to hate me as much as I hate them."

This photo was taken in 2009. One year later, these trees would be gone.***

Oddly, the Toomer’s Corner incident helped me better make peace with another incident, one that happened a few years earlier, in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan.

Unlike the Toomer’s Corner oaks, the Buddhas of Bamiyan were not trees, but two statues. Rising 38 and 55 meters high, they had been carved from the sandstone cliffs of the Bamiyan Valley about 1,500 years ago—roughly 1/2 the life of the General Sherman and 1/3 the life of Methuselah—during the heyday of the ancient Silk Road.

Although the once-thriving Buddhist community had left the area centuries ago, like the Tree of Ténéré, the Buddhas of Bamiyan had lingered to become landmark of sorts, a remnant of a more temperate age.

Until they were destroyed by dynamite in 2001.

Like the Toomer’s Corner oaks, the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed by those who wanted to erase something valued by a rival—in this case by a faction of Afghan Muslims removing any trace of Buddhist idolatry.

The larger of the two Buddhas of Bamiyan, before and after destruction.****

It is tempting to see this as an expression of human intention. It is tempting to become outraged, to insist that this act, and others like it, are the actions of one group of humans against the legacy of another—be they Buddhist or Muslim or Western or Eastern or Wealthy or Poor.

Humans destroy what humans build, after all.

But then, how does this explain our behavior toward trees—which are neither built by nor beholden to any religion, culture, or creed?

There is in Japanese culture a concept called あわれ (pronounced ah-wah-reh). It’s often explained as "the wistful foreknowledge of transience and death."

However, that is not a complete definition.

A deeper way to understand あわれ is through another tree—the cherry—whose beautiful sakura blossoms are revered in Japanese culture. Many people look forward to the annual hanami (花見, literally “flower viewing”) as a day in the park with friends and family, to have sake and light picnic fare, and regard the exquisite sakura.

Cherry blossoms in Ueno Onshi Park. I was super lucky to catch them.****

But, what gives this celebration its special meaning is the knowledge that in a few days, the sakura will disperse with the wind and fade from view.

This exuberance within overwhelming transience reveals the heart of あわれ. As we celebrate, we acknowledge that we are no different from the blossoms, and our actions no different from the wind.

And so, perhaps the wind that scatters the sakura is the wind that causes us to push against the trees, the statues in our own lives.

Beyond the good, evil, logical… and even the inexplicably stupid…perhaps all we do is a simply a consequence of our mortality.

And that all we'd so easily call intention is instead a deeper celebration of a fate that all creatures, from the briefest flutter of sakura to the most ancient bristlecone pine and beyond, have no choice but to share.

--

Please Subscribe!

Next Week--Crappers and Titzlings and the Earl of Sandwich.

Cover: Michel Mazeau - http://www.agadez-niger.com/photos_users/r_1705-1-arbre-du-tenere-en-1961.jpg, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4240288

*Dieter Schaefer/Collection: Moment Open/Getty Images

**By Holger Reineccius - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=912634

***By Robert S. Donovan from Adams, NY, USA - rollin' Toomer'sUploaded by merbenz, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21732078

****By Buddha_Bamiyan_1963.jpg: UNESCO/A Lezine; Original uploader was Tsui at de.wikipedia.Later version(s) were uploaded by Liberal Freemason at de.wikipedia. Buddhas_of_Bamiyan4.jpg: Carl Montgomeryderivative work: Zaccarias (talk) - Buddha_Bamiyan_1963.jpgBuddhas_of_Bamiyan4.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8249891

*****My own photo.