You Are Here: The Hubble Deep Field, the Cosmological Principle, and Why We Might Be Special After All

If stars are bright, and space is infinite, shouldn’t everywhere you look be a star? Shouldn’t the night skies be a wall of light?

Hi Folks!

Why is space so dark?

If stars are bright, and space is infinite, shouldn’t everywhere you look be a star? Shouldn’t the night skies be a wall of light?

This is called Olbers’ Paradox, after the astronomer Wilhelm Olbers, but I think many kids have thought about it. I know it used to bug me.

Wilhelm "Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet?" Olbers*

I think it bugged me because none of the answers seemed to make total sense. Yes, the universe was not infinitely old. Yes, not all light is visible. Yes, the universe is expanding. Yes, space might be full of dust, too.

Sure. All true. But none of these patchwork answers had that “Aha!” moment.

And then came the Hubble Deep Field (HDF).

The HDF was released to the public in 1996—not even 30 years ago.

To create the HDF, the Hubble was not pointed at a specific object—and that was the point. The goal was to find a ”typical” patch of sky—and see what the Hubble could see.

With no nearby pesky stars or galaxies blocking the view, astronomers expected to see some faraway galaxies. But no one could have predicted what they found would change the way humans thought of the universe.

Because, with the Hubble Deep Field, space was never so dark again.

As Hubble was doing its thing, other instruments were mapping the Cosmic Microwave Background—the literal echo of the Big Bang—with unprecedented scope and detail. And it is everywhere, wherever one looks—one can detect this radiation.

Wherever one looks, one sees not only the light of a star—but the birth of every star.

It is a wonderful time to learn about the universe. But as we find out so much more of what is out there—what does that say about our own significance? Ptolemy may not have been right, but his geocentric universe had one thing going for it—

We were pretty darned special, weren’t we?

Since then? Less and less so.

✨💫🌠⭐️🤩

By 1980, in his landmark series Cosmos, Carl Sagan could say the earth was merely, “A tiny speck of rock and metal, shining feebly by reflected sunlight.”

Carl Sagan!!! But if this were current, that space behind him would not be so empty.*

Which is a definite step down from the Center of All Creation.

It’s been a little bittersweet. As humans advance in science, technology, our ability to look farther, more precisely, more dispassionately tells us more about where we are. Yet, with each advance, where we are seems to become less and less significant.

As for who we are?

In a 1995 interview, Stephen Hawking said:

“The human race is just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet, orbiting around a very average star in the outer suburb of one among a hundred billion galaxies.”

And, considering that was Stephen Hawking, that seemed to be the end of human specialness.

But science has no end. Astronomers keep looking. And they keep finding.

The first exoplanet was discovered in 1992. It was almost nothing like our own Earth—or our own sun—but it was something. Before that, weren’t sure if other stars even had planets.

The first exoplanet orbiting a G-class star, like our sun, was made in 1995, the same year as Hawking’s interview. As detection techniques improved, more planets—and more types of planets—were found.

With these findings came a very direct way to test Sagan and Hawking’s somewhat metaphysical assertions. If we were really ordinary, then we should expect to find a lot of planets and star systems like ours.

The more we look, the more we find.

With better and better detection methods, we now know of over 5000 exoplanets, and more are being found every day. Planets seem to be everywhere. Big planets, small planets, gas planets, ice planets…there are “hot Jupiters” and “super earths” and “eyeball planets” and even planets made of solid diamond.

And yet, we have not found a single planet that approximates our earth.

✨💫🌠⭐️🤩

In fact, out of the thousands of planetary systems we’ve discovered, we have not found any remotely like our Solar System.

Our sun? Actually, quite unusual. First off, it is a G-type main sequence star. “Main sequence” is very much a Sol-centric term, since, by a huge margin, most stars are K and M-type red dwarves.

And, even for a G-type main sequence star, the Sun is an outlier, with five times less active (fewer prominences and solar flares) than average for its type.

Going back Hubble’s and other galactic discoveries, we’ve found that even our galaxy is extraordinary—though it might superficially resemble other spiral galaxies, it is also quite calm, with an abnormally placid central black hole.

So, based upon our current observations, we are on a unique planet in a unique solar system, orbiting a very uncommon star, in a strangely anomalous galaxy.

Our Earth might be more special than Ptolemy could have imagined.

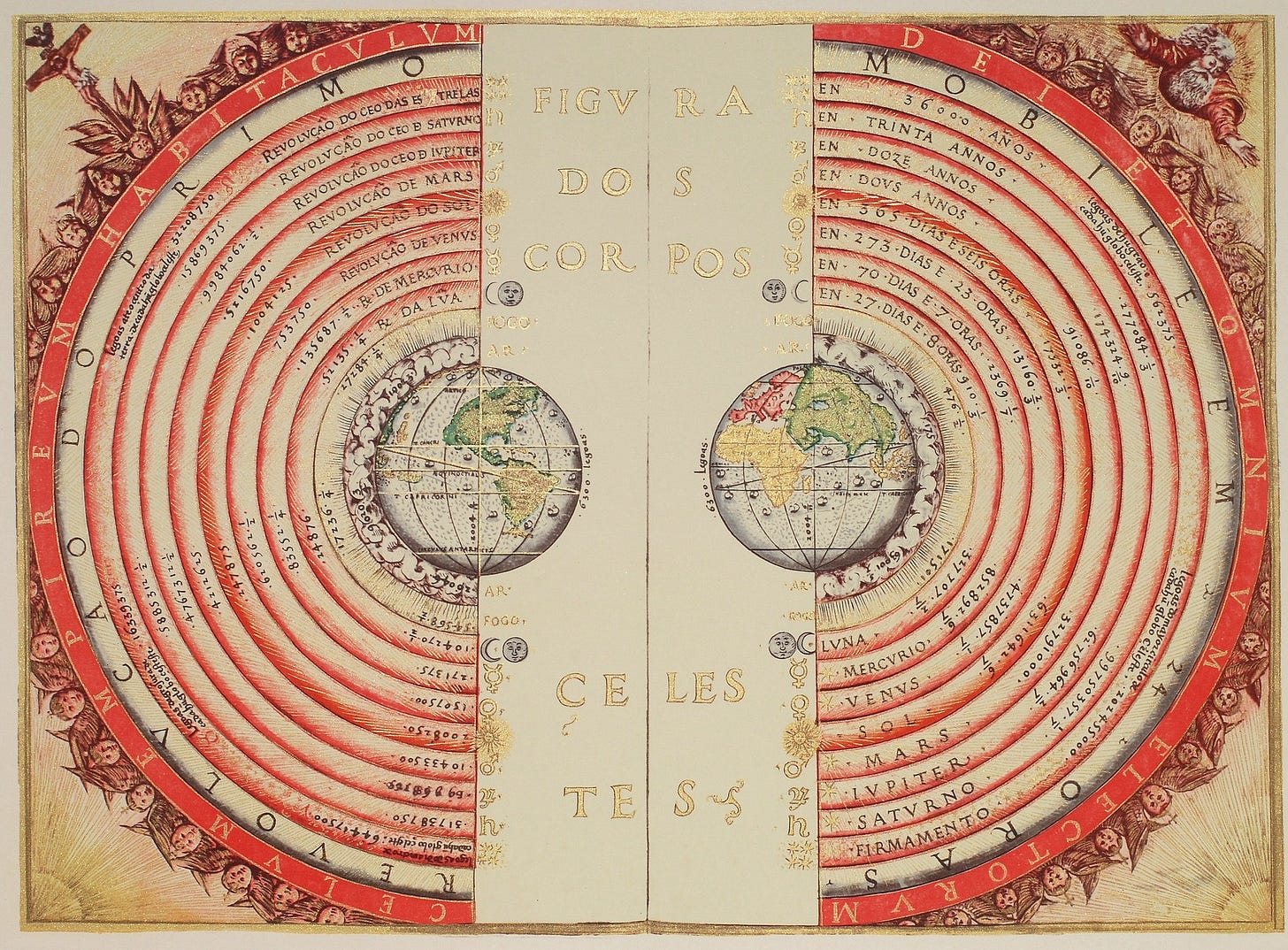

Ptolemy--horribly wrong, but pretty darned grand.**

And, as far as “chemical scum?”

Hawking was a genius, but he was limited by the information available at the time. Without our capabilities and data, both Hawking and Sagan chose to apply a concept called the Cosmological Principle—that over sufficiently large scales, the universe is all the same.

Sagan says, “In what is the likelihood that only one ordinary star, the Sun, is accompanied by an inhabited planet? Why should we, tucked away in some forgotten corner of the Cosmos, be so fortunate?”

But there is a problem with this application.

How large is sufficiently large?

From space, the Earth is a roundish object in hydrostatic equilibrium (a sort of flattened sphere). But on the ocean, or an airplane, or even a tall building, the horizon looks pretty flat in all directions. And, if you live in Switzerland and never saw the rest of the world—you would never know that it is not filled by mountains and glaciers and rivers and freshwater lakes.

Then again...if you live in Gruyères, why leave?***

We ain’t the entire cosmos. Applying the Cosmological Principle to who and where we are requires strange combination of the humility and hubris.

Humility, to assume we could possibly be as “ordinary” the rest of the cosmos. And hubris, to assume that our perceptions are expansive enough to invoke the Cosmological Principle in the first place.

In fact, even our time in the universe is extraordinary.

Between the early Big Bang years and the eternity before, and the endless future of dark energy and fading red dwarves ahead—there is one beautiful instant where stars of all types and galaxies can appear.

Between eternities lies this one glimmering slice of time, where a telescope looking deep into the night sky can see a field of sparkling possibilities.

Guess where we are?

✨💫🌠⭐️🤩

I think about this as I think of other spaces, the spaces between each of us. Technology brings closer to the different types of language, of sexualities and genders, and of religions and family structures—it is natural to feel that we’ve lost a bit of specialness, of our uniqueness.

It would be easy to resist that change, to say the Earth is the center of the universe, to assert the Earth is flat, to say that customs and peoples outside of our village must somehow be wrong.

It is easy to feel threatened by others, by who they are and how they live, to feel as if we’re losing ourselves.

But perhaps we just need to look more closely. If we really look at other people, do we really lose ourselves? How is that even possible?

If I remember who I am, what I have done, I’ve loved, what I dream at night—can I really say that I am mere “chemical scum?”

What about you?

The Cosmic Microwave Background. You are Here.****

It takes humility to entertain the possibility of being lost in an insignificant corner of humanity—but it is hubris to think that any of us could possibly be ordinary.

The more we look, the more we find.

In each of us, even now, in all the galaxies Hubble could ever see.

Even now, as I write these words to you.

--

Next Week: TBA, but probably something a little closer to home. We've been in space a lot. ;)

Cover: R. Williams (STScI), the Hubble Deep Field Team and NASA/ES

* Tony Korody /Collection:Sygma/ Getty Images

**By Bartolomeu Velho - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3672259

***Cjeiler, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

****European Space Agency, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons